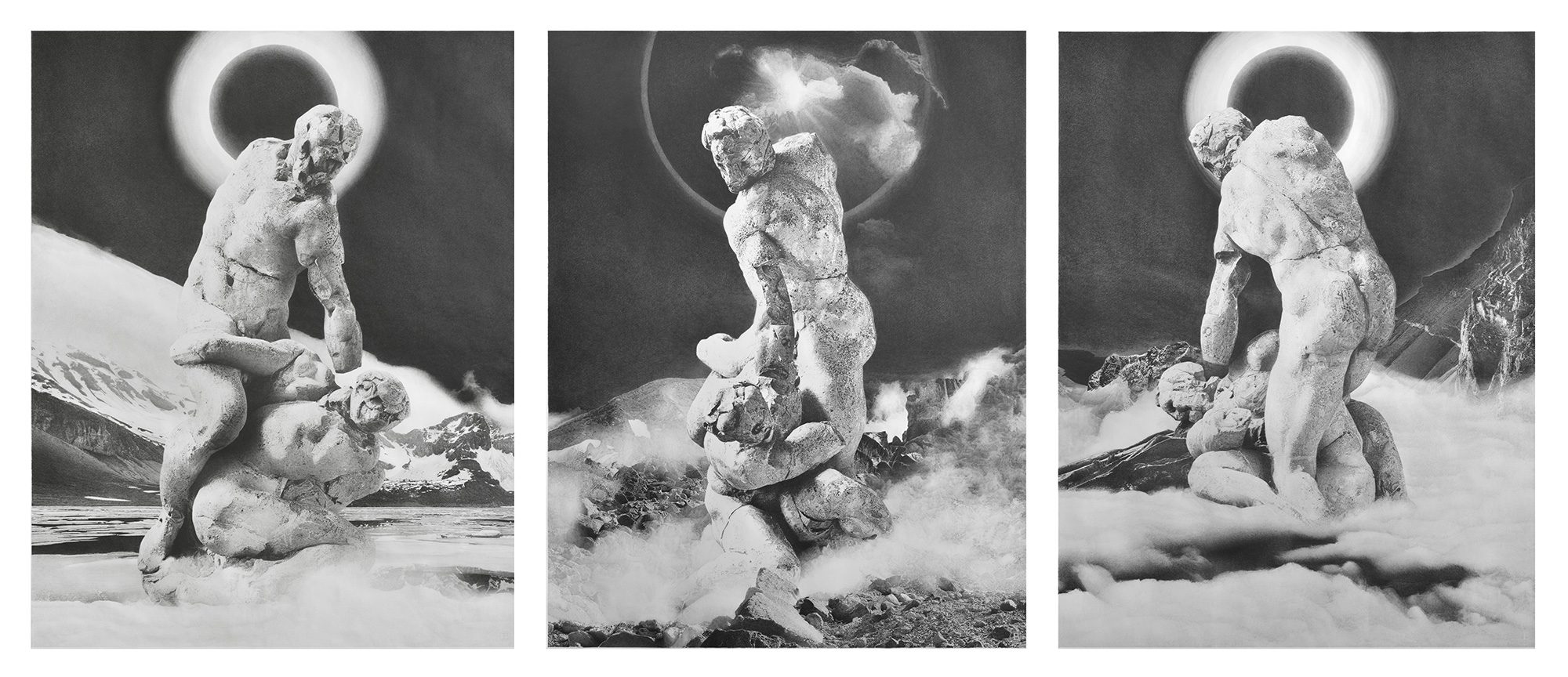

Jean Bedez

Hercule et Cacus, 2020

Drawing with graphite pencil, Canson paper 224g/m2

Triptych, 180 x 140 cm each, framed

70 7/8 x 55 1/8 in.

Jean Bedez’s drawings offer images of the contemporary world that work as allegories: of political and religious power, of showbiz society, of the role of the citizen. They explore the relationships of domination in our societies.This triptych is inspired by a very damaged sculpture by Michelangelo from 1530, depicting the fight between Hercules and Cacus. In this work, the great Hercules, victorious over Cacus, is himself defeated by the passage of time. The arm holding his weapon has disappeared, the features barely human. On the verge of collapse, it’s a fragile and damaged figure of power that we see fighting the darkness of this surreal landscape. He is currently exhibited at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

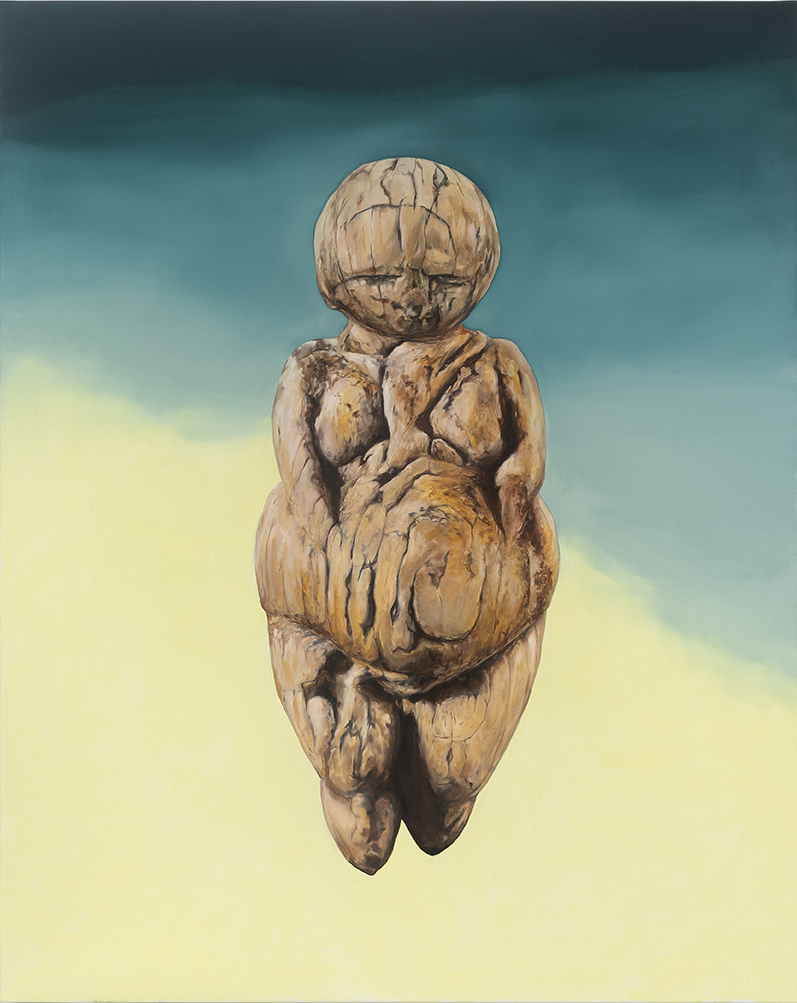

Romain Bernini

Ghost of Our Love, 2020

Oil on canvas

200 x 160 cm

78 3/4 x 63 in.

In Romain Bernini’s latest series, prehistoric Venuses stand out against an abstract, multicolored background. These figures come from afar, from an ageless world, of a distant primitivity. And the artist places them in the foreground, reversing the linear order of time, the primordial figure going before the abstract period, to the point that they sometimes become almost Pop. The titles refer to famous love songs of the XXth cenury, underlying the persistance and deep connexion between art and desire. His prehistoric Venus nested in abstraction also touches on the question of aura, the aura that photography has lost, according to Walter Benjamin, and that contemporary painting seeks to recover. His work tends more profoundly to show the vitality, the refound pleasure of this art, as other regimes of images threatened to prompt its disappearance.

Alin Bozbiciu

Choreography of the Present, 2021

Oil on linen

200 x 315 cm

78 3/4 x 63 in.

Alin Bozbiciu quickly established his pictorial vocabulary. An atmosphere of melancholy hovers on his canvases, something he acknowledges: “Painting always has a certain closeness to death, something that disturbs you and does not leave you at rest.” He limits his palette to shades of blue, purple, gray, and pink, with only a few bright colors, sometimes outlining the bodies of the figures in his paintings. “I would like my paintings to be like landscapes seen from very far away. I never use paintings straight out the tube, strong colors too often give the impression of being artificial”.

Gil Heitor Cortesão

The Crossing #6, 2019

Oil on plexiglas

72 x 177 cm

28 3/8 x 69 3/4 in.

Gil Heitor Cortesão uses the ancient technique of “fixé sous verre” (reverse painting on glass) to create paintings with a strange atmosphere, in which water takes a vital part. Pools, floods and rainy landscapes on dreamlike architectures offer a meditation on light, transparency and artifice.

Jörg Immendorff

Sammler, 1982

Oil on canvas

126 x 121 cm

49 5/8 x 47 5/8 in.

About the stars of Jörg Immendorff, he did several paintings with this star shape as central figure. In the first paintings it was a block of ice floating on water, reference to the Cold War and the division of Germany. It also refers to the red Soviet star, and this symbol in Immendorff’s painting was understood as a provocation and lack of support towards West Germany. Immendorff protested that the West German government was trying to infantilize artists for them to support their politics.

Eva Jospin

Forêt, 2020

Cardboard and wood

97 x 130 x 39 cm

38 1/4 x 51 1/8 x 15 3/8 in.

Eva Jospin (born 1975, FR) develops her work with patience, and it is with patience that one must contemplate, and even experience them. The artists works with cardboard, in theory a raw, unappealing and simple material, to create volume and perspective. A dichotomy lies at the heart of her work, between the violence of the gesture (tearing appart and lacertaing cardboard) and the subtelty of the finished work, when it comes out finely crafted. A long work of cutting, assembling and superimposing allows her to chisel forests, at once dense and delicate, enigmatic and quiet. To observe them constitutes a mysterious and troubling experience, they draw mental and oniric landscapes leading us deep into “those districs of the soul where monstruous vegetations of thought extend their branches” (Huysmans, Against the Grain, 1884.)

Youcef Korichi

Etre dedans, 2015

Oil on canvas

195 x 130 cm

76 3/4 x 51 1/8 in.

Youcef Korichi paints desolate urban landscapes, men with timeworn faces, busy hands and rubbish skips dumped on the pavement. His scenes and portraits are inventions: the artist does not draw from the ambient mass of images, but puts together the scenes in his painting bit by bit (or almost), working as a genuine observer. His own works contain many subtle references to the Old Masters – indeed, painting and its history are probably the main theme of his work. But his work also shares a contemporary form of romanticism, a register typified by waste grounds, city limits, abandoned places, with a sense of the cruelty of our world. For the people and objects painted by this artist all bear the marks of time, are wrinkled and worn. His world is anything but smooth and clean.

Kriki

Punkitude, 2019

Oil on canvas

170 x 250 cm

66 7/8 x 98 3/8 in

Kriki first appeared in the context of the 80’s, driven in France by the « Free Figuration », with artists such as Combas or Di Rosa, and echoing both American graffiti and German neo-expressionism. His paintings manipulate the original images from which they emerge from, resisting our initial attempts at a reading in order to express themselves in a universal language. Kriki claims that whilst his paintings come from a skilful blending within a relatively congested pictoral space, they are not any the less « open » : one element leads to another that leads to another and so on, like a waterfall effect or a row of falling dominoes. This results in paintings that resemble rhizomes and determine all sorts of arborescence. They all share the same rythm, in a kind of treasure hunt that leads the spectator from one corner to another, then remixing everything they saw and work out the meaning or start over.

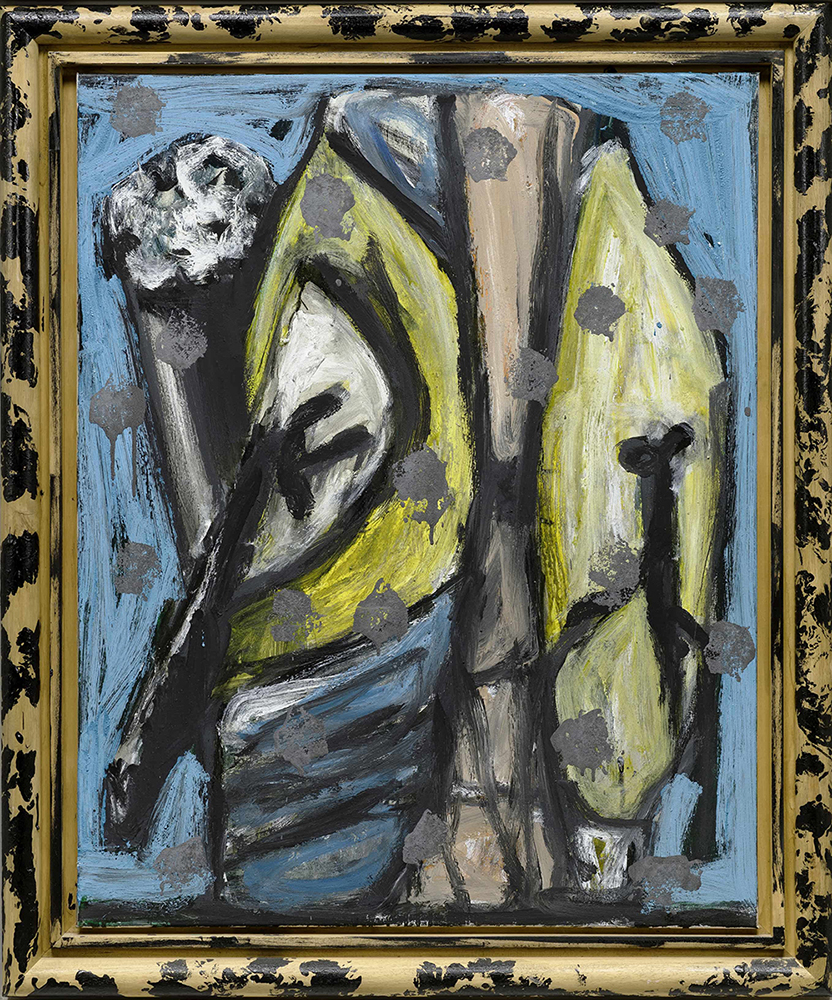

Markus Lüpertz

Gelbe Fenster, 2009

Oil on canvas

100 x 81 cm

39 3/8 x 31 7/8 in.

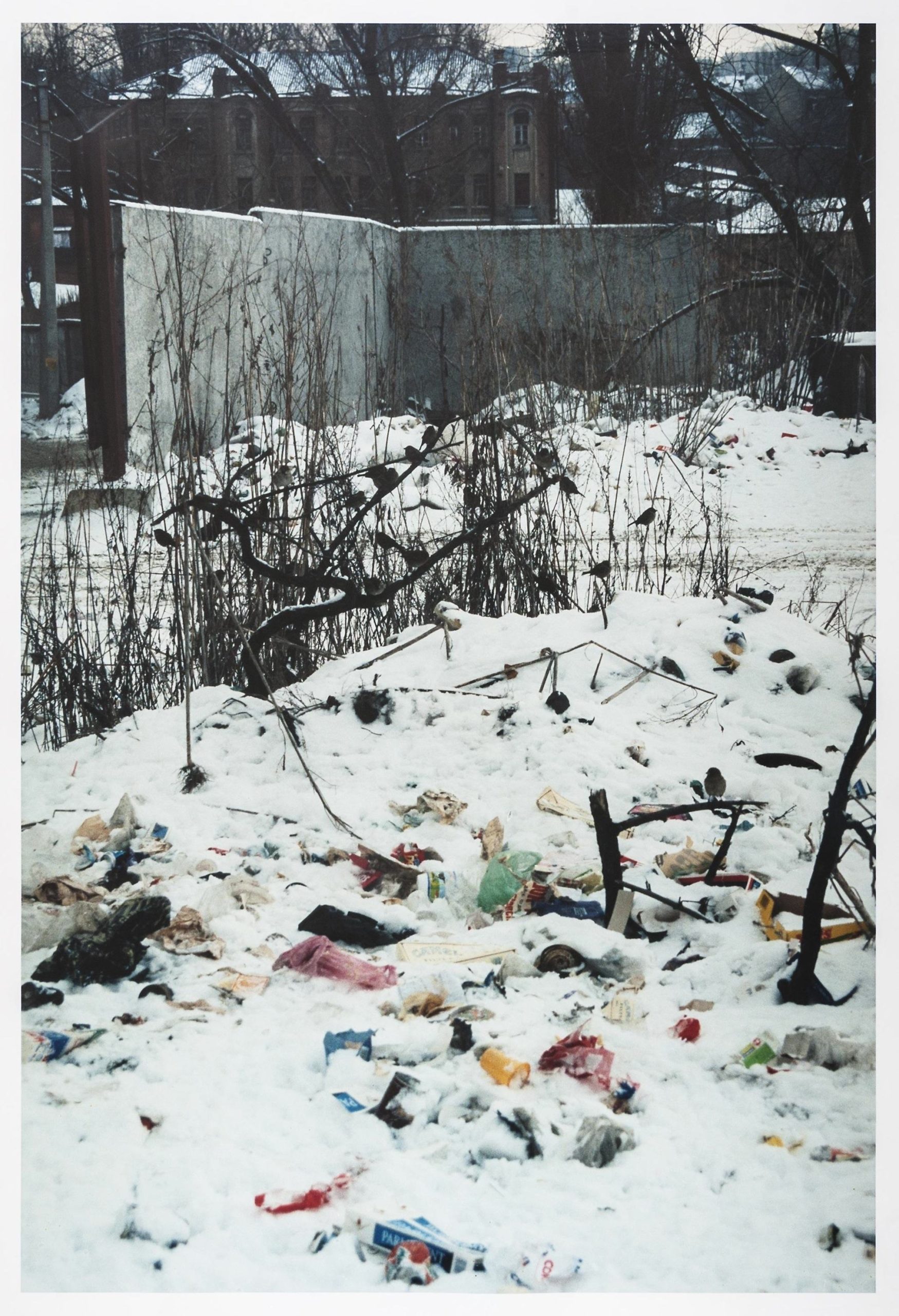

Boris Mikhaïlov

Untitled from Case History, 1997-1998

C-print

179 x 126 cm

70 1/2 x 49 5/8 in.

Edition 3 of 5 + 2 AP

Ukrainian-born Boris Mikhailov is one of the leading photographers from the former Soviet Union. For over 30 years, he has explored the position of the individual within the historical mechanisms of public ideology, touching on such subjects as Ukraine under Soviet rule, the living conditions in post- communist Eastern Europe, and the fallen ideals of the Soviet Union. Although deeply rooted in a historical context, Mikhailov’s work also incorporates profoundly engaging and personal narratives of humor, lust, vulnerability, aging, and death.

This body of work was exhibited for the first time in MoMA, New York. in 2011. It explores the deeply troubling circumstances of people who have been left homeless by the collapse of the Soviet Union. Set against the bleak backdrop of the industrial city of Kharkov, Mikhailov’s life-size color photographs document the oppression, devastating poverty, and everyday reality of a disenfranchised community living on the margins of Russia’s new economic regime. Mikhailov recalls of his experience returning to Kharkov some years after the collapse of communism, “Devastation had stopped. The city had acquired an almost modern European centre. Much had been restored. Life became more beautiful and active, outwardly (with a lot of foreign advertisements)—simply a shiny wrapper. But I was shocked by the big number of homeless (before they had not been there). The rich and the homeless—the new classes of a new society—this was, as we had been taught, one of the features of capitalism.” One of the most haunting documents of post-Soviet urban conditions, Mikhailov’s pictures capture this new reality with poetry, clarity, and grit.

Shanthamani. M.

Upside Down Tree, 2016

Fiberglass, steel, resin

172 x 150 x 147 cm

67 3/4 x 59 1/8 x 57 7/8 in.

Unique

Shanthamani Muddaiah uses natural materials, especially charcoal from trees and bamboos, to create sculptures and drawings. Her Upside Down Tree (2019) is a suspended inverted tree, evoking the major ecological challenges of our time, the accelerated processes of development and urbanization, and the depletion of natural resources.

Juergen Teller

Vivienne Westwood No. 6, London, 2009

Digital c-print

293 x 202,5 cm, framed

115 x 79 3/4 in.

Edition 1/3

Considered one of the most important photographers of his generation, Juergen Teller is one of a few artists who has been able to operate successfully both in the art world and the world of fashion photography. Teller’s provocative interventions in celebrity portraiture subvert the conventional relationship of the artist and model. Whatever the setting, all his subjects collaborate in a way that allows for the most surprising poses and emotional intensity. Driven by a desire to tell a story in every picture he takes, Teller has shaped his own distinct and instantly recognisable style which combines humour, self-mockery and an emotional honesty.

Anne Wenzel

Attempted decadence (Blossoms, large, blue), 2014

Glazed ceramics

151 x 120 x 107 cm

50 1/2 x 47 1/4 x 42 1/8 in.

Anne Wenzel uses sculpture and ceramic to embrace forms of representation that are deeply anchored in the legacy of commissioned art (portrait, allegorical bust, still-life) and carry out a series of actions that shift these images of power into a precarious space, causing official symbols and traditional codes to waver into a twilight, wistful realm. Anne Wenzel’s dark manner exemplifies an approach to history that is haunted by violence. It confronts monumental stability with the threat of downfall and chaos, the serenity of timeless nature with signs of its extinction and decay, the hieratic idealised portrait with signs of havoc and upheaval.